Daily Grind: Midwest VCs on the rise, work vs. play, and setting intentions for the week

The Daily Grind is a short newsletter to start your day: One startup news headline, one page from a great book, and one question for reflection

Hello!

Welcome to Day 2 of The Daily Grind, your daily morning newsletter to catch up and kick off a great day.

I hope you had a great 4th of July weekend. I had a fun time with friends and my wife, but now it’s time to switch gears and build!

Up today: Great news for Midwest startups, a 98-year-old wisdom on work and play, and an intention-setting question to start your week.

📰 One Startup Headline: Ohio’s Drive Capital Defies the Odds

$500 million in one week? Not bad.

On July 5, Columbus-based Drive Capital made the news for distributing half a billion dollars of winnings to its investors. Most of the return came from two investments: Root Insurance and Thoughtful Automation.

But the real story is how a Midwest VC has found a way to thrive by investing everywhere except Silicon Valley.

Drive Capital currently has $2.2 billion under management and has employees in six cities: Columbus, Chicago, Austin, Boulder, Atlanta, and Toronto. There strategy has 4 legs:

Focus on “boring” industries. Where startups in Silicon Valley often aim for novelty, Drive’s focus is on disrupting old, forgotten industries, like auto insurance (Root), dental insurance (Beam Benefits), and farmland Fintech (Acretrader).

Invest where the customers are. According to TechCrunch, Drive’s heartland presence allows it to “backs founders who would otherwise face a choice between building near their customers or their investors.”

Columbus, for example, is considered a nearly perfect representation of America on average, making it a testing location for major food and retail brands. If you’re building products for the average American, this is a good place to be.

“Settle” for unicorns over decacorns. Many valley-based VC funds have gotten so big, they need decacorns ($10B+) or even centacorns ($100B+) to make their returns. Drive raises relatively smaller funds ($1B in 2022) and is satisfied with $1-3B outcomes.

Be first, be the only. Due to the three pillars above, Drive Capital is often the first and only VC backing its companies. “About 20% of the companies in our portfolio today, we are the sole venture firm in those businesses,” said founder Chris Olsen. Because of this, Drive’s stake in its portco’s is around 30% on average, compared to 10% for Valley firms.

Read the full story: https://techcrunch.com/2025/07/05/drive-capitals-second-act-how-the-columbus-venture-firm-found-success-after-a-split/

Drive Capital has had its ups-and-downs, but it’s arguably the biggest driver of innovation in the Midwest today (outside our academic institutions). They have a strong presence here in Chicago, and their city GM, Landon Campbell, is a local startup super connector.

Follow his newsletter for weekly Chicago and midwest startup news.

A Few Good Links:

It’s always hard to pick just one headline to cover, so here are a few more stories worth exploring:

NPR: Elon Musk forms new party after split with Trump over tax and spending bill

Techcrunch: At least 36 new tech unicorns were minted in 2025 so far

Brian Balfour: The Next Great Distribution Shift (ChatGPT)

This post is from June 18 but I just discovered it and still obviously relevant

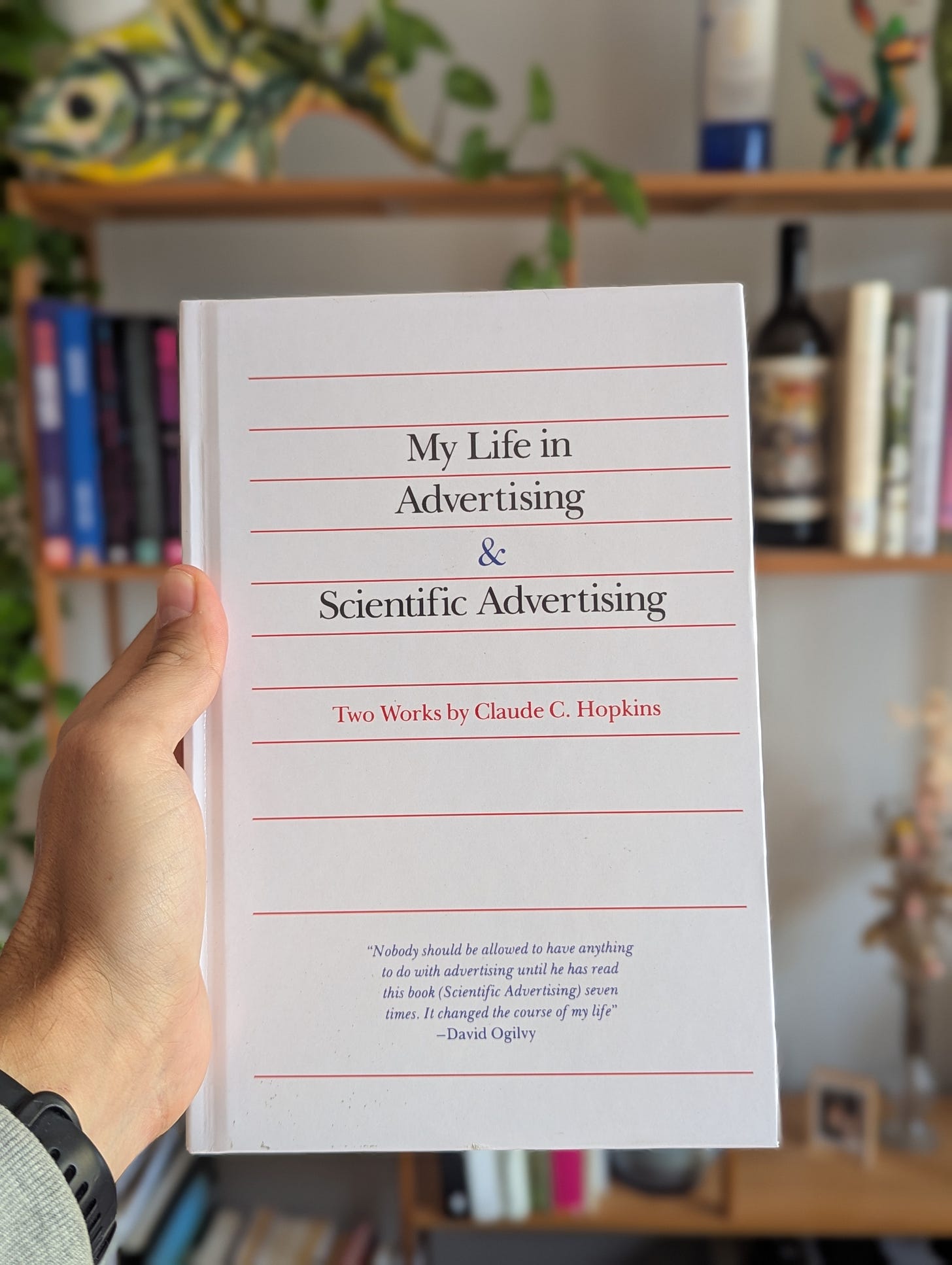

📚 One Page: My Life in Advertising by Claude C. Hopkins

Midwest-born and raised, Claude C. Hopkins wasn’t just the father of modern advertising, but in many ways American capitalism. He created demand for products all of us take for granted. If you’ve ever owned a vacuum cleaner, it was because of him. He took on products ranging from canned meats to tires to pharmaceuticals and elevated each to household staples.

He’s most famous for his first book, Scientific Advertising (1923), but his second, My Life in Advertising (1927), is just as good. I found this page on his early influences a helpful reminder that we can shape our reality (and therefore, our fortunes) to meet our goals.

Another man exerted a remarkable influence on my impressive years. He was a railroad section foreman, working for $1.60 per day. He bossed several men whose wages were $1.25 per day.

…

The foreman worked with enthusiasm. He said: “Boys, let us lay so many ties today. Let us get this stretch in fine shape.” The men would go at it stoically, and work as though work was a bore. But the foreman made the work a game.

That man built his home in the evenings, after ten-hour days on the railroad. He cultivated a garden around it. Then he married the prettiest girl in the section, and lived a life of bliss. Eventually he was called to some higher post, but not until I learned great lessons from him.

“Look at those boys play ball,” he said. “That’s what I call hard work. Here I am shingling a roof. I am racing with time. I know what surface I must cover before sunset to fulfill my stint. That’s my idea of fun.”

“Look at those fellows whittling, discussing railroads, talking politics. The most that any of them know about a railroad is how to drive a spike. They will always do that and no more. Note what I have done while they loafed there this evening—built most of the porch on my home. Soon I will be sitting there in comfort, making love to a pretty wife. They will always be sitting on those soap boxes around the grocery stove. Which is work and which play?”

“If a thing is useful they call it work, if useless they call it play. One is as hard as the other. One can be just as much a game as the other. In both there is rivalry. There’s a struggle to excel the rest. All the difference I see lies in attitude of mind.”

I never forgot those talks. That man was to me what James Lucey was to Calvin Coolidge. I can say to him now, as Coolidge said, “Were it not for you I should not be here.”

In later years I became a director of the Volunteers of America and made a study of life’s derelicts. I studied them in the soup kitchens, in prisons and on parole. Their great trouble was not laziness, but too much love of play. Or, rather, a wrong idea of play. Most of them had in their youth worked every waking hour. But some worked at ball-throwing while others hoed the corn. Some pocketed balls while others pocketed orders. Some of their home runs were recorded in chalk while others’ were carved in stone. All the difference lay in a different idea of fun.

I came to love work as other men love golf. I love it still. Many a time I beg off from a bridge game, a dinner, or a dance to spend the evening in my office. I steal away from week-end parties at my country home to enjoy a few hours at my typewriter.

So the love of work can be cultivated, just like the love of play. The terms are interchangeable. What others call work I call play, and vice versa. We do best what we like best. If that is chasing a polo ball, one will probably excel in that. If it means checkmating competitors, or getting a home run in something worth while, he will excel in that. So it means a great deal when a young man can come to regard his life work as the most fascinating game that he knows. And it should be. The applause of athletics dies in a moment. The applause of success gives one cheer to the grave.

For the record, I am all for some fun and games (I play competitive ultimate frisbee and take it way too seriously). But this is a great reminder that our perception of things matters, and it’s malleable.

❓ One Question for Reflection

It’s a Monday—after a holiday no less—so let’s start the week by setting good intentions:

Imagine it’s this Friday at 5pm. You just finished the week, and you look back extremely satisfied with how you spent your time. What made this week a success?

Focus on “how you spent your time” vs. “results.” Most of the results we want aren’t completely in our control. But spend your time wisely and the results will eventually follow.

🗳️ Wrap Up and Feedback

That’s it for today’s Daily Grind! I’d love to hear what you think of this new format. Take the poll below and reply with any feedback or ideas.